As someone who has long been fascinated and inspired by what we can learn by mimicking nature’s patterns, the field of permaculture feels like one I could study and practice for a life time and never run out of more to learn. Permaculture has various definitions, such as the science of resilience or how to design in ways that regenerate nature, i.e., that not only sustain but restore to leave things healthier than when we started.

Network Weaving Based on Ecological Design

This weekend I attended the New Hampshire Permaculture Gathering, held at D’Acres, a permaculture farm and educational homestead that models many kinds of permaculture designs and practices. Dave Jacke, co-author of Edible Forest Gardens and ecological designer/practitioner, offered a talk about Ecosystem Mimicry, inviting us to explore how we can learn to “mimic ecosystems in the design of everything we do in our cultures.” He shared principles that we can use to “design cultural systems that minimize stress and competition, and maximize cooperation, harmony, productivity, and diversity, while allowing each community member to remain true to their intrinsic nature.”

He explained the principles using examples related to ecosystems and farming, yet I was struck by how the principles can be used in our work with social change leaders, as we help them design ways of collaborating to maximize cooperation and enable each player to do what they do best. He reminded us: “we are nature, working” and the principles of ecology apply to us. One of the shifts we need to make is in our own mindsets, e.g., from taking the lesson from nature of “survival of the fittest” to looking more carefully to see the sophistication of how nature uses cooperation as much or more than competition.

Dave shared designs that you find in nature and that we, as system designers, can mimic. The key is to look at the system as a whole to create the conditions where the interaction of the parts generate ‘emergent properties’ – that is, more valuable outcomes that only arise from the collaboration. This is not the way we are trained to think. In permaculture, these are described as guilds – designs for how to grow plants together that generate symbiotic mutually beneficial relationships. The relationships among the parts are different in each. I appreciated this nuance, as we often talk about collaboration generally, but it is helpful to appreciate there are different “blueprints” for how the parts work together.

I’ll describe a couple of the guilds here and illustrate how these can be models for collaborating for social change:

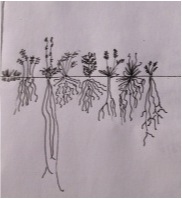

Resource Sharing Guild (or Resource Partitioning Guild) – In Edible Forest Gardens, this guild is defined as “a group of species that have a similar way of making a living (i.e., the same community niche) that partition resources so they can compete minimally.” For example, a group of plants all need to use the resource of soil for nutrients. Researchers dug up and studied the roots  systems of adjacent plants and found a mix of some that were shallow and broad, others that were deep tap-roots, and others in the middle. The plants had evolved a cooperative way to all access the same resource, while reducing competition and stress. Healthy diverse ecosystems repeat this pattern for other resources such as, sunlight or pollination services, e.g., some plants flower early, some late, etc. so that the pollinator insects can focus on each in turn with a steady supply over time, rather than all flowering at once.

systems of adjacent plants and found a mix of some that were shallow and broad, others that were deep tap-roots, and others in the middle. The plants had evolved a cooperative way to all access the same resource, while reducing competition and stress. Healthy diverse ecosystems repeat this pattern for other resources such as, sunlight or pollination services, e.g., some plants flower early, some late, etc. so that the pollinator insects can focus on each in turn with a steady supply over time, rather than all flowering at once.

Social change work example: One way to think of this is a community of practice, where people who do similar work or play a similar role in a system come together and align their work. Here are a couple examples:

- A foundation hired us to work with a group of non-profit organizations in a city that all offered coaching to high school students to help them get into and through college. We surveyed the group to index and compare what each organization did, e.g., types of students they work with, geography they focus on, services they offer. This was summarized/visualized in a big table so people could see gaps and overlaps and the group could self-organize to better serve the community and students. For example, a few organizations specialized in helping immigrant students address their unique barriers, no organizations focused on veterans, some offered bi-lingual services. This enabled people to enhance a focus on a niche they serve well and allowed referrals and partnerships to develop.

- In the Vermont Farm to Plate Network, a work group was formed of technical assistance providers who help farms and farm-based businesses through all the phases of their development and growth. This group developed a similar index/map to see who offered which services for which stages of business development, as this blog describes.

A focus on resource partitioning can ensure the system offers support to all needs of it’s target audience. It’s also helpful to remember that healthy systems have redundancy, so having multiple organizations play key roles is not a bad thing; it enables the system to be more resilient.

Mutual Support Guild – In Edible Forest Gardens, this guild is defined as “a group of species with dissimilar community niches that form networks of mutual aid.” The needs of one species are met by the yields of others. A classic one is a planting that Native Americans created called the “three sisters,” where they planted beans, corn, and squash together. Here are a few of the mutual support elements in this combination:

- The corn plant grows tall and provides the structure for the bean plant to climb.

- The bean plants ‘fix’ nitrogen from the air into the soil, a key nutrient that helps the corn and squash grow.

- The squash plant grows low to the ground with wide leaves that shade the ground so weeds can’t grow, helping the other two plants thrive by reducing competition.

Social change work example: When various parts of a system/community are brought together to focus on how they can greater collective impact, it offers the opportunity to discover these combinations of mutual support. For example, I used to work with a non–profit called Sustainable Step New England and we offered training in sustainability principles to help leaders in business, government, and communities adopt these strategies. Through the Boston Green and Healthy Building Network, we met up with Health Care Without Harm, which had broad connections and technical expertise in the health care sector. The two organizations quickly saw how we could collaborate in ways that combined the unique capacities of each organization to do more together. We wrote a joint grant, which led to many years of productive work greening the health care sector in Greater Boston.

This is one small example with two organizations. Collaborative networks working to change large systems offer many opportunities to combine the complementary capacities and skills of various organizations and people to generate greater results. For example, the Vermont Clean Water Network, brings together more than 75 non-profit organizations, local, regional and state government agencies, businesses and individuals to work collaboratively to create a culture of clean water.

As we look at weaving collaborations and networks, there is much to learn from how nature has evolved models of collaboration to generate mutual and systemic benefits.