Mapping Prejudice in Minneapolis engaged citizens in doing research to create maps that visualize how historic racist practices in real estate drove racial segregation that persists to this day. I learned about it from Janne Flisrand, a network weaver friend who is active in civic affairs there. She said it was instrumental in building the political will that enabled the city to adopt a groundbreaking Minneapolis 2040 City Plan, that has gotten national attention.

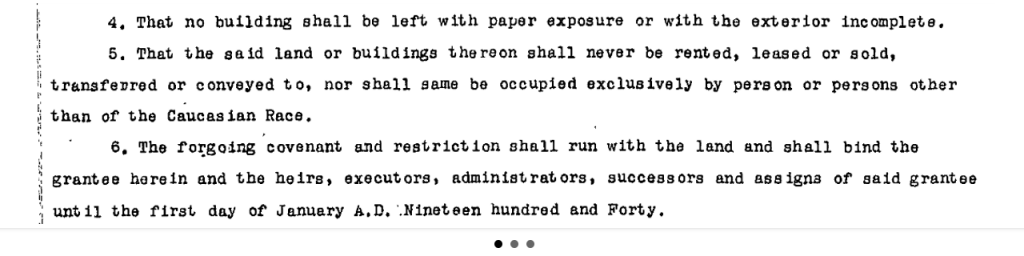

In Minneapolis, as in many cities, racially-restrictive deeds blocked access to home ownership and opportunity for people of color. Here’s what made the Mapping Prejudice project so powerful, in Janne’s view:

- This historic data existed, but it was inaccessible. This project made that available to researchers, citizens, and policy makers.

- How they did this labor-intensive research was powerful. They engaged citizens in reading historic documents – ultimately over 177,000 documents from the county were read, taking thousands of hours of volunteer time.

- People took a workshop to learn how to do it and learn about how this history was hidden. The language in the legal documents was much more explicitly racist than people imagined, and this impacted people. They could see the deeds for their property and others in their neighborhood. After the workshop, people kept volunteering.

- Together, their work fed into a database that became the source for a blog with story telling and animated maps showing how the racial covenants spread over time. It spurred people to rethink their view of the past, share about their own experience, connect it on a personal level and talk to friends about it.

City staff working on the Housing part of the Minneapolis 2040 plan participated in these workshops and saw the research. It informed how they framed the housing part of the plan and what was needed, i.e., seeing how the tools of racial covenants, exclusionary zoning, and redlining excluded people of color, those with low income, and renters from many parts of the city. They could connect that to today’s data on disparities and look at how this plan could change those patterns.

The 2040 Plan ends exclusionary zoning and allows triplexes everywhere. Minneapolis is the first city of its size to do this. Another great facet to the story is how the City engaged the public in an intentional way to prioritize getting input from people of color, low income, and renters (who are traditionally under-represented in public engagement processes). The City’s web site says:

“Throughout the Minneapolis 2040 process civic engagement has been designed and conducted in a way to create equitable and innovative ways to engage populations that have been historically underrepresented in civic life.” The Minneapolis 2040 web site details the many creative ways they carried out this intention. If you are tired of the refrain of “how can we get more diverse voices to the table?,” you will see how they changed assumptions of ‘one table’ or evening public meetings as the ways to get public engagement.

“Throughout the Minneapolis 2040 process civic engagement has been designed and conducted in a way to create equitable and innovative ways to engage populations that have been historically underrepresented in civic life.” The Minneapolis 2040 web site details the many creative ways they carried out this intention. If you are tired of the refrain of “how can we get more diverse voices to the table?,” you will see how they changed assumptions of ‘one table’ or evening public meetings as the ways to get public engagement.

Artists played a key role, as you’ll see in Janne’s blog Minneapolis’ Secret 2040 Sauce was Engagement. How racism operates systemically can be hard to convey and communicate. I admire how Minneapolis combined mapping history as it impacts the present, citizen participation in research to make that history visible, and widespread public dialogue to create a future different than the past. This Atlantic magazine article found what Minneapolis did so unique it conducted a detailed review of how the reformers pulled it off. It said: “In Minneapolis, housing advocates have succeeded by shifting the focus of public discussion toward the victims of exclusionary zoning. More important, advocates also showed public officials and their own fellow citizens just how numerous those victims are.”